Up next: Today @

10:00 AM

ASHLEY COLACO

Newsletter

Now Playing

Recently Played

Bad Reputation

Joan Jett/Blackhearts

4 minutes ago

Would You Fight For My Love

Jack White

8 minutes ago

ebay Purchase History

Faye Webster

12 minutes ago

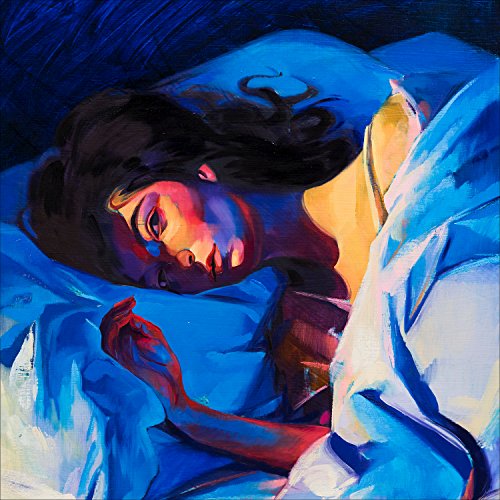

Perfect Places

Lorde

15 minutes ago

gray light

soccer mommy

18 minutes ago

Half

PVRIS

23 minutes ago

A-Punk

Vampire Weekend

25 minutes ago

Another Dimension

Daniel Donato / Elle King

29 minutes ago

catch these fists

Wet Leg

32 minutes ago

Dirty Laundry

All Time Low

36 minutes ago

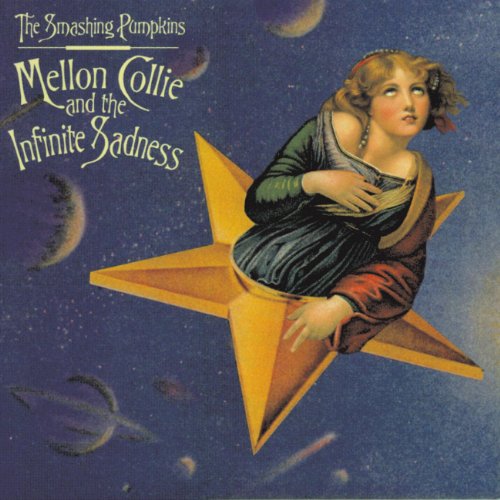

Cupid De Locke

The Smashing Pumpkins

38 minutes ago

Painkiller

Spirit Animal

42 minutes ago

Guy Fawkes Tesco Dissociation (Radio Edit)

jasmine.4.t

46 minutes ago

Daughter

Tara Terra

50 minutes ago

How Come You Never Go There

Feist

54 minutes ago

I'm Not Ready

Geena Kaye

57 minutes ago

Pork and Beans

Weezer

60 minutes ago

Shake Shake

Chad Sugg

Over an hour ago

Cobra

Geese

Over an hour ago

What Difference Does It Make?

Smiths, The

Over an hour ago

National Monument

SNST

Over an hour ago

Up We Go

Lights

Over an hour ago

El Manana

Gorillaz

Over an hour ago

Keep Me in the Dark

Flock of Dimes

Over an hour ago

It Gets Better

COUNTERFEIT.

Over an hour ago

A Whiter Shade of Pale

Procol Harum

Over an hour ago

Where's My Phone?

Mitski

Over an hour ago

Nausea

Beck

Over an hour ago

All My Dogs

Sam Truth

Over an hour ago