A cursory interpretation of For Emma and Forever Ago reads Bon Iver’s first album as a direct address to whatever woman damaged our fragile-voiced singer–just look at the title. While that doesn’t describe For Emma… perfectly, it’s what made me so fond of the sparse record. According to Grayson Curison’s intimate Pitchfork interview with Justin Vernon, Vernon insists that, “[For Emma…] was more about me than anything. Emma isn’t a person as much as it’s a place and a time.” What significance can be gleamed from Bon Iver’s second record being self-titled? In fact: its not self-titled. In the aforementioned interview, Vernon says, “…I named this record Bon Iver, Bon Iver— half self-titled, half weird thing– because I see Bon Iver as this opportunity to stay in something.” The title fits: if For Emma… was about Vernon–recorded primarily by himself, alone in the woods–then Bon Iver, Bon Iver is synthesis of Vernon’s cryptic songwriting, his keen ear for sound experimentation, and his impressive gang of musical collaborators. Bon Iver, Bon Iver is fuller, more rounded than For Emma…, yet Vernon’s quiet harmonies and vulnerable melodies remain. Perhaps the album’s title is an exaltation of everything Bon Iver can be–“Good winter, good winter!” Vernon has left his cabin.

With the exception of three songs, every song on Bon Iver, Bon Iver is titled after a place, either real or imaginary. At risk of sounding pretentious, each song seems to recreate its title’s “sonic space”. Take “Perth” for example: a guitar melody opens the record and keeps the song simple, until the shimmering “Ahhh!” Then, a driving snare drum converges with a distorted guitar riff, warm trumpets, Vernon’s vitreous falsetto and a pounding instrumental climax. Fade out to a echoy guitar melody that takes us to a new “place” familiar yet new. Bon Iver, Bon Iver forgoes a lyrical narrative to instead provide snapshots, images, and vague feelings. Vernon rejects traditional form and allows sounds and melodies to dictate where each song is going (there’s no sing along choruses like “Skinny Love”). The biggest similarity between For Emma… and Bon Iver… is the honest emotion of both records. Take the album’s final two tracks: “Lisbon, OH” quietly plods for a minute and a half of bleeps and bloops until it finally finds what it was looking for–the opening chords to “Beth/Rest”. A culmination of cheesy R&B synthesizers and the twangy country guitars–“Beth/Rest” is so earnest in its weirdness both musically and its lyrics about burning-star-fire-love. It’s a fitting final swell for an album of grand climaxes.

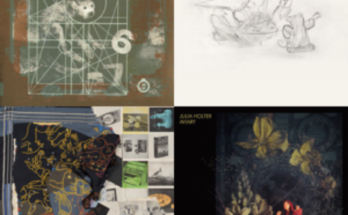

When an artist releases a sophomore record it’s tempting to choose a superior. That wouldn’t make sense with Bon Iver’s output, however, because each record has contrary intentions. Even the album art on Bon Iver, Bon Iver is a direct contrast to its predecessor. For Emma’s… art is a picture of a barren winter tree–naked branches disguised by cold splotches of gray, green, and white. The art on Bon Iver, Bon Iver is a detailed painting of a peaceful cabin. The ice just melted and a shimmering lake reflects the trees and sky. The scene is so full of life the trees are tearing off their canvas. It’s uncanny how well Bon Iver’s cover art describes the record inside its sleeve. Dense and layered, full of strange sounds and studio flourishes: a record that demands to be explored. The frost has broke and the result is warm and inviting.