The word ‘bluegrass’ is music to my ears, and if you enjoy the band the Grateful Dead, you

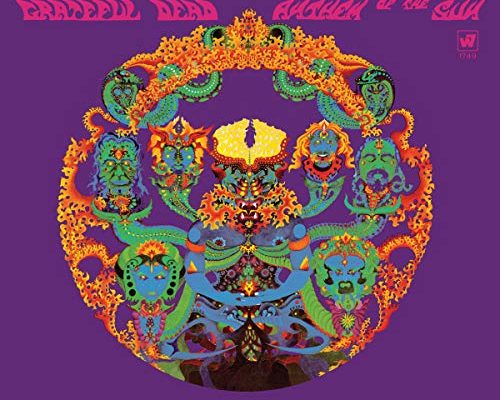

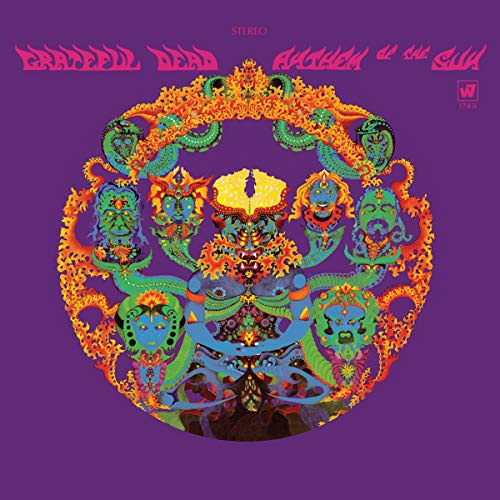

understand where I’m coming from. Although Jerry Garcia might not shred the electric guitar on Earth anymore, the music of the Grateful Dead still lives on through many music festivals and concerts today, such as the Dead and Company. In 1968, the original band came out with the album “Anthem of the Sun,” comprised of five songs embodying the typical folk styles the band carries.

The Grateful Dead in general doesn’t follow any type of rhyme or reason to their musical style, considering their songs usually range from 5–15 minutes with no absolute pattern of chorus and verse separation. That’s something I’ve always appreciated about this band. They were often found performing for crowds that tried their best to carry certain energy of no boundaries. With that being said, this band found their sounds with repeating genres but with no rules to their music. This meant their songs seemed like a never-ending head-bobbing method of enjoyment, free of responsibility other than enjoyment.

The first song “That’s It For the Other One (Part I–IV)” is a seven-minute song dedicated to the ins

and outs of how to feel the unity of the universe and absolutely nothing else. It generally follows the kind of whimsical situational lyrics that presents the main singer being faced with a dream-like entity that opportunities him with death itself to which he writes a song in memory. I particularly enjoy how the Grateful Dead can create plenty of scenarios with an unspoken mutual understanding of what it must’ve been like for the people involved. I’m sure the people in the crowd could relate to the verses within these songs because they found themselves constantly using the Grateful Dead as a crutch for understanding their own life situations. Throughout festivals like Woodstock, members of the audience would find themselves dancing to death in solemn agreement and pure enjoyment to the music they played for it so intimately connected to what they believed.

Another memorable song in this album is “Born Cross-Eyed,” written and produced by Bob Weir. The style of this song resembles the style of the Beatles with a swing style rhythm and frequent falsetto harmonies. Although records find Bob’s dyslexia was the perpetrator for the song’s lyrics, I find the general premise of the band might also admire the actual psychotic features of spending time frequently partaking in actions that brought the spirit closer to death, like spending trips around the sun dancing and speaking to earlier mentioned entities. The band also found itself hand in hand with the Beatles as they would refer to a bus of bright colors that would bring them fortune or happiness once they decided to get on.

I absolutely adore the song “Alligator” because of its immaturity. There’s nothing wrong with hearing Phil Leish tell you to ‘get up and dance’ in the middle of a 15-minute song about alligator folklore. The Grateful Dead artfully incorporated the rebellion of drug use and psychedelia into the realistic imagery that was offered in folklore as literature. This song, for example, was solely about an alligator’s life–hanging out and doing alligator things. But the song is not deemed any less important as it is filtered between beautiful motivational remarks and electric guitar solos with jumpy drum beats that cannot be listened to without a little personal bopping. Without a certain swing, a listener would be forcibly holding themselves back.

In plenty of their songs, there’s a certain ‘getting down’ where there are no vocals and the instruments are absolutely grinding and building up, all working together for some apparent climax. This resembles the emotion put towards the stories they shared through their music, as though it didn’t matter if it was through the dancing, instruments, lyrics, or just stories themselves that were begging the listeners to hear the message. It wasn’t simply one; it was all. In modern times, there is no shortage of this folk-type jumping and dancing that takes place at these concerts, and I genuinely believe if anyone has time to listen to Grateful Dead or get their feet in some grass to dance to it, it’s absolute cherishing of one’s time. The last eight minutes of “Alligator” is dedicated to this funky interaction between the freedom the guitarist brings while jamming out and the incorporative fun the audience brings while embracing the radical openness. With professional rock artists singing “Alligator” repeatedly at the end, it really resembles this futility.

The band had tunes around the theme of roads and railroads, including the final song of the album, “Caution (Don’t Stop On The Tracks),” simply another opportunity for folklore symbolism. Besides

the obvious magnificence of the song, the methods of madness the band members used were so far from the minds of production seen today. Often times, the band members would be traveling or spending time creating music where they would some idea would dawn upon them from an ambiguous source. With this song, simply hearing and spending time near a train station sparked some simultaneous agreement that a song could come from it as they saw the traditional sign. To put it simply, the moral of this song is to not limit yourself to the tracks of a ride but instead: enjoy the ride itself.