Musical plagiarism is a tricky subject. New lawsuits against artists who’ve “stolen” musical ideas from other artists crop up nearly all the time. Some of the most famous examples include allegations of Nirvana ripping off Killing Joke, Led Zeppelin stealing from Spirit, and Robin Thicke and Pharrell running off with sounds from Marvin Gaye’s hit “Got To Give It Up.”

But can we chalk up using the same chord progressions, similar bass riffs, or even just similar sounds, to musical plagiarism? After all, don’t many pop songs feature the same four chords? In this article, we’ll dive into a simplified musical analysis of one specific legal trial, and I’ll propose a few reasons why I think many of these plagiarism lawsuits are bogus and unfair.

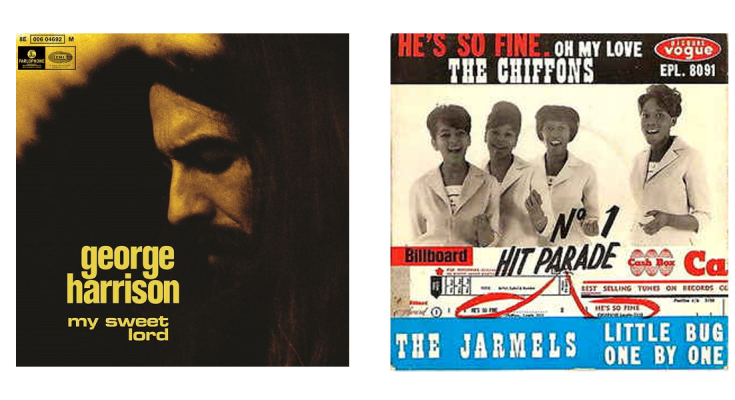

Case Study: George Harrison vs. the Chiffons

On Friday, November 27th of this year, George Harrison’s first solo chart-topping single, “My Sweet Lord”, was released on vinyl for the annual Record Store Day. In this case study, I’ll cover this song’s involvement in one of the most famous legal battles in music history.

In 1971, George Harrison, a former member of the Beatles, released “My Sweet Lord”. Just months after the release of the song, Harrison and his publishing company, Harrisongs Music, found themselves embroiled in legal trouble with Bright Tunes Music after being accused of plagiarizing “He’s So Fine” by The Chiffons. Before we break down the similarities and differences of each song, have a listen to both and compare them yourself.

My Sweet Lord: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SP9wms6oEMo

He’s So Fine: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rinz9Avvq6A

They sound similar, no? The main reason for this is that both songs use the same chord progression in their verses (ii7 – V) and a similar chord progression in their choruses. And if we take a look at both melodies side by side, we can pinpoint some similarities.

These are two lyrical excerpts from the choruses of both songs, with the top belonging to Harrison’s “My Sweet Lord” and the bottom belonging to The Chiffons’ “He’s So Fine” (both transposed to be in the same key for easy comparison). In each lyrical phrase, we see a similar melodic contour (i.e., the notes follow an ascending pattern, then they jump back and forth a bit, and hold a single note before jumping into the next phrase). And this seems to be the offending excerpt–one in which the melody seems similar and the chord progression is nearly identical.

But I firmly believe that Harrison did not rip off The Chiffons. You can’t copyright a chord progression. And as we can see in the excerpts above, even in the most “incriminating” piece of evidence, in this case, we find quite a few reasons why this melody is fundamentally different. For one, they don’t begin on the same notes relative to the key. Second, The Chiffon’s section of the melody is longer in terms of rhythmic duration and is slightly less melodically complex.

And we can make similar arguments throughout the rest of the song. Harrison’s introduction was different, and his song included more complex guitar riffs. The melodic content, while similar, has key fundamental differences. There are important rhythmic and timbral differences that define each song as being uniquely their own.

Harrison even testified in court that he drew inspiration not from “He’s So Fine”, but from “Oh Happy Day,” a gospel song that was in the public domain and was perfectly legal to use in new works. We can clearly hear the similarities between this song and Harrison’s–and as a byproduct, the similarities between it and “He’s So Fine.”

So, had these factors been taken into account during the investigation, Harrison might’ve won the lawsuit, instead of being ruled guilty of “subconscious plagiarism” and made to pay half a million dollars in damage royalties and suffer through one of the longest plagiarism lawsuits in music history.

In Summary: Why Musical Plagiarism Lawsuits are Flawed

- Music isn’t made in a vacuum.

To quote Mark Twain, “There is no such thing as an original idea”. Indeed, all artists draw their inspiration from the work of others that came before them. New musical works are built from other influences and recycled to create a new variation that can never be truly original.

Take popular chord progressions, for example. If you’re familiar with Western music theory (or you’ve seen the Axis of Awesome’s parody song, “4 Chords” that I linked to earlier), you may know that many American pop songs use the same [I V vi IV] chord progression. Does this mean that Journey, James Blunt, The Beatles, Lady Gaga, and so many others are ripping each other off? I don’t think so. Chord progressions are the recycled basis of the vast majority of these pop songs. But each song has its own defining characteristics, such as different melodies, rhythmic elements, instrumentations, and timbre. Which leads me to my next point:

- Many legal authorities don’t have the musical expertise to claim a song was plagiarized.

Anyone can listen to two songs and recognize that they have similar musical content. But when it comes to legal disputes, musical experts should be called in to hash out the details and present the facts. And in many lawsuits, this isn’t the case.

In 1984, John Fogerty of Creedence Clearwater Revival had to testify in court by bringing his guitar up to the witness stand so that non-musicians could better understand his stance. He played portions of his song alongside the one he allegedly ripped off, and demonstrated elements of both compositions that were similar, and more importantly the elements that made them distinct compositions.

And he ended up winning the court over–but had he been able to present his points to a professional musician or music scholar, he would’ve taken less of a risk. And those pop artists who can’t give a demonstration like Fogerty’s may be out of luck.

- Many artists never even listened to the music they’re accused of stealing from.

I always like to give artists the benefit of the doubt. When Sam Smith claims he’s never heard of Tom Petty’s “I Won’t Back Down,” we can only take him at his word. And did Katy Perry really plagiarize a small Christian rapper’s music for her hit single “Dark Horse”? It’s possible but unlikely. There are many musical decisions an artist makes when writing a song, but it’s entirely possible for two musicians to make very similar choices with no malintent.